A hiring committee now reads fewer sentences than a spam filter. A learning platform can reach millions and still fail to teach anything. We have never been better connected, and rarely more uncertain who or what we are talking to. The problem is no longer access. It is structure.

Most writing about information still relies on a comforting myth: that more data leads to more truth, and truth to better decisions. When this fails, we call it misinformation and move on. What we almost never question is whether information was ever designed to tell the truth in the first place. This is how we argue about content while ignoring networks.

Yuval Noah Harari’s Nexus: refuses that comfort. It tracks information not as knowledge but as glue what binds people, institutions, and machines into formations that act. Truth is optional. Connection is not.

Harari earns this reframing through history rather than prophecy. One early episode recounts Cher Ami, the carrier pigeon that carried a message through German fire to save the Lost Battalion in 1918. The pigeon does not understand the message. Meaning belongs to the network that can receive and act on it. Infrastructure, not insight, determines survival. Information works even when no one involved knows why.

From there, the book dismantles what Harari calls the naive view of information: the belief that scale and transparency naturally converge on wisdom. Some of the most powerful human networks, religious canons, totalitarian states, modern bureaucracies were built on stories that coordinated behavior effectively, regardless of their accuracy. They failed ethically, not operationally.

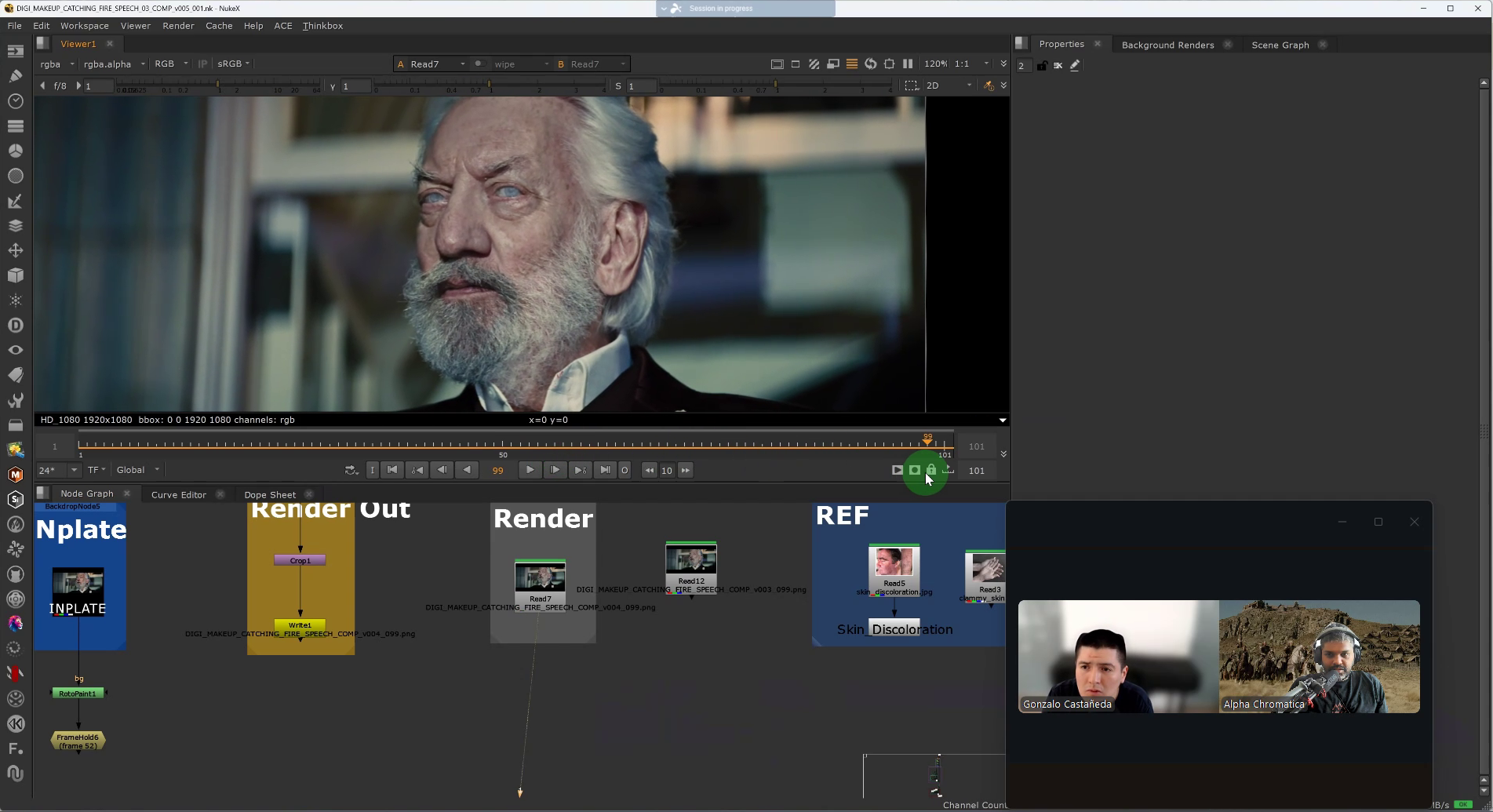

Method matters. Harari works comparatively, moving between military archives, religious canonization, epidemiology, and contemporary AI research. He studies institutions the way an engineer studies stress fractures: not to moralize, but to identify failure modes. The book’s structure mirrors its argument, alternating myth and bureaucracy before confronting a new kind of actor AI systems that do not merely transmit information but generate decisions.

The book’s limit is its ambition. By explaining so much through networks, it risks flattening incentives, labor, and coercion into secondary effects. Not every coordination problem is epistemic. Some are simply enforced. Still, the lens holds.

I recognized the argument’s force not because it was unfamiliar, but because it removed a defense I still use that good information, properly delivered, is enough.

Seen clearly, the danger is not that our systems fail, but that they succeed exactly as designed.

Discussion