There's a specific kind of book that ruins you in a good way. The kind that changes how you process information so fundamentally that you can't go back to who you were before reading it.

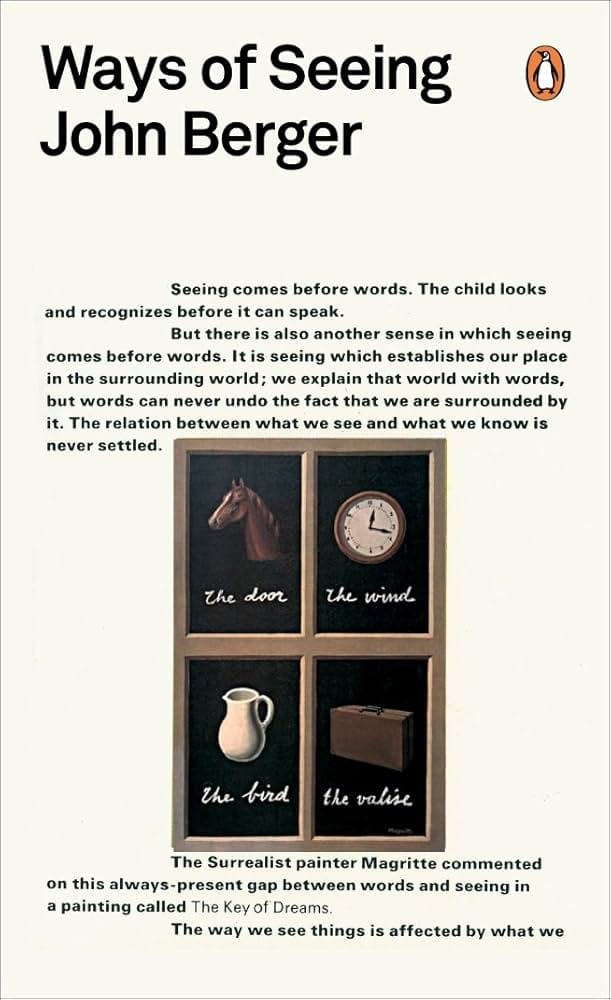

John Berger's 𝗪𝗮𝘆𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗦𝗲𝗲𝗶𝗻𝗴 is short. Around 150 pages, half of them just pictures. I grabbed it because someone mentioned it in a thread about visual literacy, and the title seemed interesting enough.

I didn't expect it to stay with me the way it has.

Berger doesn't write like an academic. He writes like someone showing you a magic trick, then immediately explaining how it works, which somehow makes it more fascinating instead of less. His main argument is straightforward. The way we look at things isn't neutral. It's been shaped by centuries of assumptions we inherited without realizing.

He demonstrates this through juxtaposition. A painting from the 1600s next to a modern cosmetics ad. A portrait of a wealthy merchant next to a car commercial. The similarities are glaring once you see them. The poses. The lighting. The way objects are arranged to communicate status and desirability.

Some chapters have no words at all. Just sequences of images placed in a particular order. At first this annoyed me. I wanted explanation, context, something to grab onto. But that's the point. He's forcing you to do the work of interpretation instead of passively absorbing someone else's conclusions.

The chapter about women in European painting was the one that stuck. Berger points out that for centuries, the nude wasn't just a subject. It was a specific genre with specific rules, and those rules were designed by and for men. Women in these paintings aren't really people. They're arrangements of flesh meant to communicate that the owner of the painting has good taste and disposable wealth. The woman herself is incidental.

He puts it bluntly: men look at women, women watch themselves being looked at. And once you notice this pattern, it's everywhere. Magazine covers. Film posters. Instagram. TikTok. The infrastructure of looking hasn't changed nearly as much as we pretend it has.

Discussion